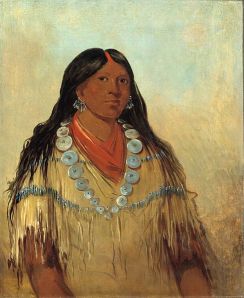

George Catlin, “Tchow-ee-pút-o-kaw,” 1834

The indigenous peoples of the American Southeast lived alongside one another long enough that many of their beliefs about the little folk have at least partially blended together. Carolyn Dunn has written a short article on Southeastern little people that draws from several cultural sources. The picture that emerges from such a cross-cultural survey of the little folk is more often than not quite coherent. If we think of little folk as a species, then we are dealing with a number of closely related subspecies that generally display the following characteristics:

- These creatures are very good at not being seen. They are selective about whom they permit to see them at all—generally only children or medicine people.

- They are more often mischievous than truly evil, although their pranks can be quite destructive. It is unwise to speak disrespectfully even of those who are well-disposed toward humans, however, as they are quick to take offense.

- They are often more kindly hearted toward children, often leading them home when they get lost in the forest.

- They live deep in the forest or in other out-of-the-way natural settings.

- They are often (but not always) associated with the healing arts. Many of these groups, in fact, serve as spiritual helpers to healers and herbalists and are often instrumental in initiating youngsters into the healing arts.

Here are five types of Southeastern little folk arranged roughly from north and east to south and west.

Yunwi Tsunsdi

There are two prominent groups of faery-like beings in Cherokee legend. There are the nunnehi, tall “spirit warriors” who are indistinguishable from ordinary humans (except for their magical powers), and the yunwi tsunsdi (yoon-wee joons-dee) or “little people,” child-sized beings who live in the rocks and cliffs.

Like the nunnehi, the yunwi tsunsdi prefer to be invisible, although they do sometimes appear to humans. Seeing them, however, is sometimes taken as an omen of impending death. They are well-proportioned and handsome, with hair that reaches almost to the ground.

Yunwi tsunsdi are depicted as helpful, kind, and magically adept. Like many faery creatures, they love music and spend much of their time singing, drumming, and dancing. For all this, they have a very gentle nature and do not like to be disturbed. Even so, they are said to harshly punish those who are disrespectful or aggressive toward them.

In Cherokee lore, the yunwi tsunsdi are divided into three “clans” with varying attitudes toward humans. The Rock clan is most malicious, the Laurel clan is merely mischievous, and the Dogwood clan is most benevolent.

Yehasuri

These Catawba little folk, whose name can be translated roughly “the wild people,” are about two feet tall and usually depicted as hairy. They are trickster spirits that live in the forest. They often live in tree stumps and eat a varied died including acorns, roots, fungi, turtles, tadpoles, frogs and bugs.

These little folk are said to behave in ways very similar to the faeries of Europe. They kidnap children, for example, and like to braid the manes and tails of horses. Like the elves of northern Europe, their magical arrows are deadly to mortals. They are said to attack anyone who gets too close to them.

One of their favorite tricks is to prowl around after dark and place spells on any children’s clothing that had been hung up to dry. This bewitched clothing would give babies colic. Therefore, conscientious Catawba mothers would bring in their infants’ clothes at dusk, wet or dry.

Yehasuris are sometimes used as bogeymen to impress upon children the importance of good behavior. Indeed, they do seem to target children more than anyone else. The only way to stop them is to rub tobacco on one’s hands and recite a particular incantation against them.

Este Lopocke

As with the Cherokee, the Muskogee people (Creeks and Seminoles) distinguish between two sorts of little people, one taller and the other shorter. And among the shorter, some are more benign and others are more harmful to humans. George E. Lankford reports the observation of A. S. Gatshet in the 1800s that

The Creek Indians…call them i’sti lupu’tski, or “little people,” but distinguish two sorts, the one being longer, the others shorter, in stature. The taller ones are called, from this very peculiarity, i’sti tsa’ptsagi [i.e, este cvpcvke, “tall people”—DJP]; the shorter, or dwarfish ones, subdivide themselves again into (a) itu’-uf-asa’ki and (b) i’sti tsa’htsa’na…. The i’sti tsa’htsa’na are the cause of a crazed condition of mind, which makes Indians run away from their lodges. (Native American Legends of the Southeast [University of Alabama Press, 1987/2011] 133)

I don’t know if this tracks perfectly with the Cherokee distinction between taller nunnehi and a number of clans or tribes of shorter yunwi tsunsdi, but it at least seems plausible. I certainly welcome any insight readers might be able to give me!

The este lopocke or este lubutke (ee-stee loh-poach-kee) live in hollow trees, on treetops, or on rocky cliffs. Their homes can be identified by an extra thick growth of small twigs of branches in the trees. Despite their small size, they appear strong and handsome, with fine figures and long but well-kept hair. They might let their toenails grow long, however.

These beings are especially known to appear to medicine people and guide them in finding the herbs they need. Encounters with the little people are considered sacred and not to be shared.

The Muskogee sometimes speak of the little people simply as “Gee” (“Ce” in normalized spelling), meaning “little,” so as to avoid using their full name. Even the helpful ones object to being mentioned in a negative or disrespectful way.

Iyagȧnasha

The little folk of Chickasaw lore are sometimes identified as tribal ancestors who now take up residence in the forest. They are said to be about three feet tall. Although they might help those who are in trouble, they are also likely to play tricks on those who have offended them. They allow themselves to be seen only to a few, mostly hunters or medicine people.

They do, however, interact with children. Sometimes they choose a child to live among them for a while to be given special powers of healing. When this child grows up, he or she becomes a healer or herbalist. They might teach other children how to pursue game, as they are accomplished hunters themselves.

Even so, it is considered ill-advised to live near the iyagȧnashas. The Chickasaw would move away from an area if they thought there were little people there.

The worst enemy of the iyagȧnashas is the wasp, the sting of which is fatal to them.

Hatak Awasa

There are several types of little folk among the Choctaw. One, the kowi anukasha, serves much the same role as the Chickasaw and Muskogee little folk in initiating young children into medicinal lore.

Another type, simply called hatak awasa (or hutuk awasa), “little men,” are similar to both the bogeymen and little folk of European myth. Children are warned to be good lest the hatak awasa snatch them away. Although their role can be sinister, they also preserve otherworldly knowledge handed down from olden times.